[This month’s topic is about a subject that could get you hurt. Make sure you understand the risks. Do not rely on this content to keep you safe.]

Initial Planning

After you’ve visited a few summits, you may get a hankering to visit a summit that is… out of the way. Perhaps it is on a remote trail. It might require bushwhacking. This month’s topic is how to get to the middle of nowhere.

After you’ve visited http://www.sotamaps.org/, you’ll have a good idea of where your summit is located. You just need to figure out how to get there. (If you’re lucky, there will be a trail marked on SOTAmaps.)

When planning a hike to a summit, the first thing I do is to Google the name of the summit and the words trail, trailhead, or hike. If someone has written up a guide, this search will usually find it.

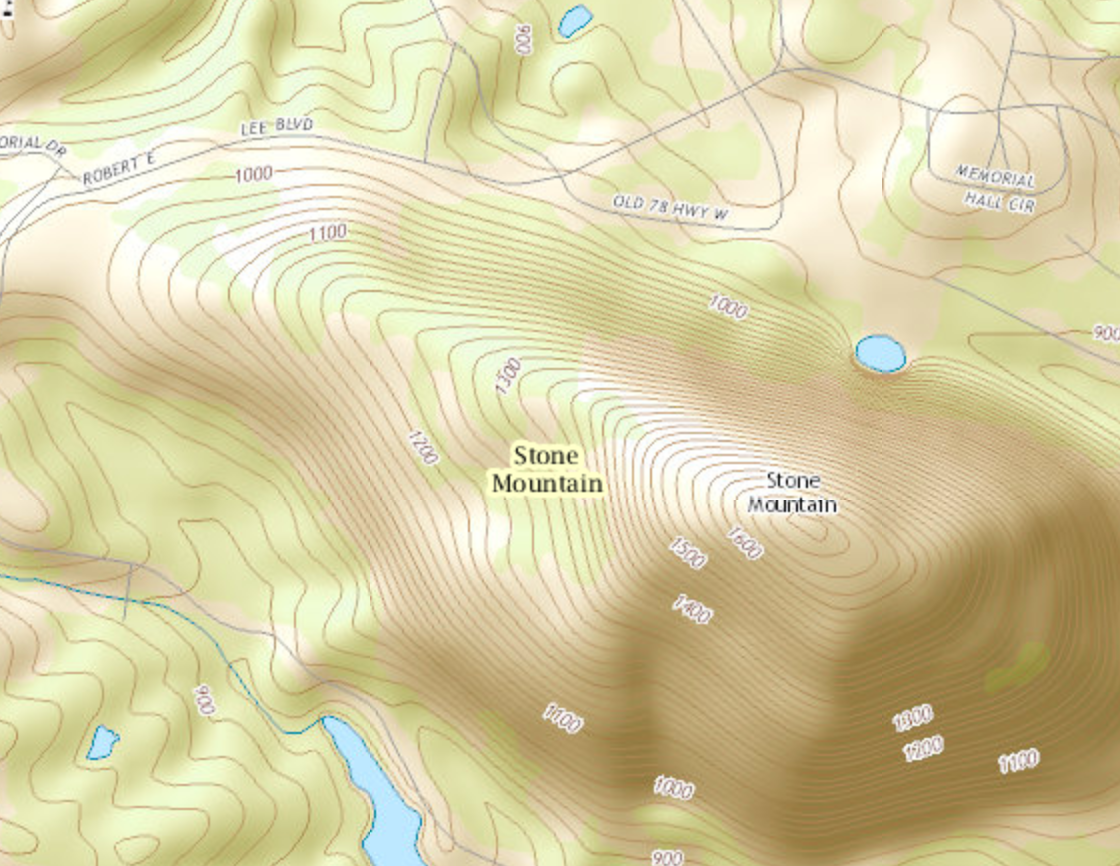

Topographic Maps

The next resource to check is a USGS topo. Visit http://store.usgs.gov and select “Map Locator & Downloader.” You can use this to download topographic maps (often called “quads” or “quadrangles”). These maps show mountains, streams, dirt roads, trails, and other geographic features. You may have learned to read these as a Scout. You can download PDF files with the exact map you would see on a paper map. These are big files; they will take time to download and your PC display them sloooowly. If you prefer, you can purchase paper maps from the same site.

There will be many editions of a map on the USGS site. I usually download the 2 or 3 most recent, look to see which is intelligible, and discard the rest. The newest edition often adds aerial imagery, which makes them tough to read.

Take a quad with a grain of salt. Just because it shows a road/trail is there, it doesn’t mean the route is passable. If you see a candidate route, use Google Earth to see if you can find evidence that the road/trail is still there. When you travel, the reality on the ground supersedes the reality on the map!

National Geographic Trails Illustrated maps are an excellent resource, if there is a map for your destination. These are much like a quadrangle, except they often contain more relevant detail.

Reaching the Trailhead

Once you’ve found a trail, you’ll need to navigate the drive to your trailhead. Google Maps has worked well for me for 90% of my back-country trailheads. Occasionally, it thinks that a power line right-of-way is a road, so watch out for unnaturally straight lines on the route. Occasionally, it will route you via a closed Forest Service road. You can check for gates on the relevant [Forest Service Motor Vehicle Use Map] (http://www.fs.fed.us/recreation/programs/ohv/ohv_maps.shtml).

A Word About GPS

When you head out into wilderness, you may elect to carry a GPS. Don’t take a GPS designed for use in a car! You don’t want a street GPS; you want a topographic GPS. I recommend using a dedicated GPS and not a smart phone app. The dedicated GPS will show your position more accurately and its batteries will last much longer. (I’ve found multiple people on the trail who were using an app who were not clear on their location.) I recommend a rainproof GPS. I have one with a tiny little screen, and I’ve never really needed a bigger display. You will want a GPS with a moving map display, and not just a latitude/longitude display.

Do not rely on your GPS to get you back to the car. Pay attention to your route. Have a plan for how to find your car if the GPS fails. Risks include electronic device failure, a geomagnetic storm, dead batteries. (I once dropped my GPS as I was crawling through rhododendron.)

Bushwhacking

If you bushwhack, navigating to a summit is easier than navigating back to the trail. If you’re on the right mountain, heading up will eventually reach the summit. When you come down, there are an infinite number of destinations you reach by heading down.

I avoid bushwhacking unless the sun is shining; I prefer to bushwhack in the winter. It is easy to travel in a straight line when you can see your shadow. If your GPS conks out, you should know the general direction to head in order to find the trail. When planning your trip, plan a fail-safe route back to the trail that has you hitting a long stretch of the trail perpendicularly. You want to know that even if you’re off course by 30 degrees, you’ve got a big target to hit.

Wrap-up

I won’t get into general wilderness safety. For that, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ten_Essentials is a good place to start.

Some really nice summits are off the beaten track. They just require a little more planning. To get you started, guides for several southeastern summits can be found at SOTA Trip Library.

See you on the summits!

73 DE K4KPK / Kevin

Where can I find out more?

- Official site: http://sotadata.org.uk/

- Mailing list: https://groups.yahoo.com/groups/summits

- K4KPK’s site: http://k4kpk.com/content/sota-menu

- Email me (K4KPK). My email address is available via http://www.qrz.com/db/K4KPK.

Bio

K4KPK, Kevin Kleinfelter is Georgia’s first SOTA Mountain Goat. His first QSO was on a SOTA activation. He has completed more than 150 activations.

This story is Copyright 2015 Kevin P. Kleinfelter. A non-exclusive right to redistribute in electronic or printed form is granted to amateur radio clubs operating in the metro Atlanta area. All other rights reserved.